By Liz, who is a volunteer with the Bawdy Courts of Lichfield project and is part of the volunteer group.

John Shaw, former churchwarden of All Saints, Derby

Elizabeth Floyde, his daughter

Gilbert, son of Gilbert Okes, native of Derby, a witness

Elizabeth, wife of Edward Moore, native of Derby, a witness

Robert Sleigh, another former churchwarden of All Saints, Derby

Doctor Clarke, assumed to be archdeacon Edward Willmote, doctor of divinity

Daniel Eyre, vicar of St Werberg, Derby

John Wyersdale, vicar of St Peter, Derby

Willington, employer of Elizabeth Moore

A single sheet is all that survives of a case brought before the consistory court in 1640. Ten names are included and it is akin to the prologue of a stage presentation: ten characters are paraded for our inspection and the plot is alluded to. The leading lady is notorious throughout the parishes of the town of Derby, but, before details of the plot can be unfolded, the final curtain is rung down.

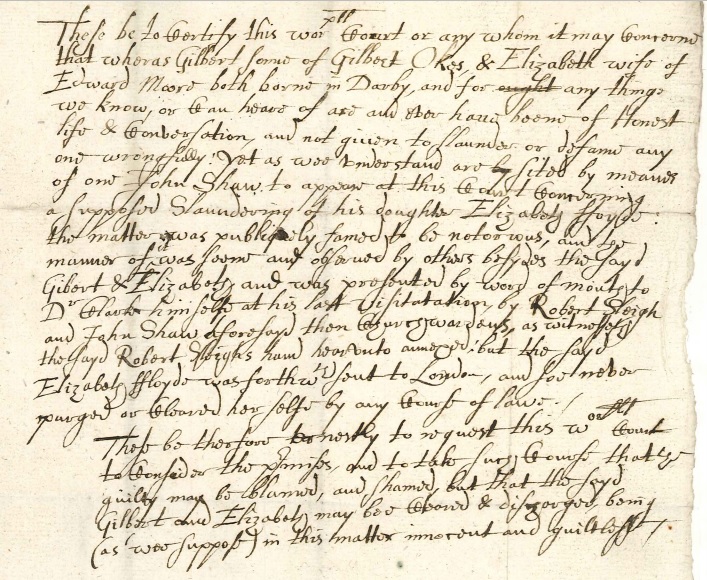

In this surviving fragment, John Shaw, former churchwarden of All Saints’, Derby, cited Gilbert Okes and Elizabeth Moore of Derby to appear at the Consistory Court to witness in a case concerning the slandering of his daughter, Elizabeth Floyd. The supposed lewdness of his daughter had already been reported verbally by John Shaw and his fellow churchwarden to Dr Clarke, presumably the archdeacon, at his Easter visitation. Three clergymen of Derby confirmed that the woman’s lewdness was commonly reported throughout the town.

Following the presentment made to Dr Clarke, Elizabeth Floyde was “forthwith sent to London and soe never purged or cleared herselfe by any course of lawe.” Who sent her? Why did she go? As her guilt had not been established, Gilbert Okes and Elizabeth Moore were left in limbo. It was the business of the court to take action “that the guilty may be blamed, and shamed, but that the sayd Gilbert and Elizabeth may bee cleared & discharged, being (as wee suppose) in this matter innocent and guiltless”. There appear to be two threads to the story: the lewdness or otherwise of Elizabeth Floyd, and the establishment and reinstatement of the good character of Elizabeth Moore and Gilbert Okes. Elizabeth Moore’s good name was vouched for by Mr Willington, whose servant she had been for five years.

In normal times the long arm of the ecclesiastical law might have pursued Elizabeth Floyde to London, or found some means of finalising the case. But these were not normal times. By 1640 the country was riven with religious and political discontent leading up to the outbreak of open warfare and bloodshed in the civil war two years later. William Laud, the high church archbishop of Canterbury, was imprisoned in 1640 for treason and subsequently executed. In 1641 the Puritan Long Parliament prohibited the ecclesiastical courts from punishing any spiriitual or moral crime, and in 1646 these courts were annulled along with the abolition of the episcopacy.

In Lichfield itself, the cathedral, home of the consistory court, was used as a fortess by both sides in the conflict. During the third siege Royalist cannon sent the centre steeple crashing down on the main roof, leaving the cathedral a useless ruin.

In the circumstances it is a marvel that the consistory court papers were preserved. This case of slander may not have concluded or perhaps never been properly filed. But somehow this single sheet, this tantalising fragment, has survived.

‘These be to certify this worshipfull Court or any whom it may Concerne that wheras Gilbert son of Gilbert Okes, & Elizabeth wife of Edward Moore both borne in Darby, and for any things we know, or can heare of are and ever have beene of Honest life and Conversation, and not given to slaunder or defame any one wrongfully: Yet as wee understand are sited by meanes of one John Shaw to appear at this Court Concerning a supposed Slaundering of his daughter Elizabeth Foyde the matter was publiquely famed to be notorious, and the manner of it was seene and observed by others besydes the sayd Gilbert & Elizabeth and was presented by word of mouth to Doctor Clarke himself at his last visitation, by Robert Sleigh and John Shaw aforesayd then Churchwardens, as witnesseth the sayd Robert Sleighs hand hereunto annexed: but the sayd Elizabeth Floyd was forthwith sent to London, and soe never purged or cleared her selfe by any Course of lawe.

These be therfore ernestly to request this worshipful court to consider the premises, and to take such course that the guilty may be blamed, and shamed, but that the sayd Gilbert and Elizabeth may be cleared and discharged, being (as we suppose) in this matter innocent and guiltless’

‘There is a common & (as we believe) a true report of the Lewdness of John Shaw’s daughter Edward Willmotte Dr of Divinity

Lub Whittington Elizabeth more was servant to mee at Least five yeares & did behave herself honestlie

Daniel Eyre vicar of St Wereburge in Darbie This former report I often heard John Wyersdale vicar of St Peters in Derby

Robert Sleigh then Churchwarde with John Shaw of the parish of all Saintes in Darby when the matter was broched who certfyed dockter Clarke of ye report of it at his visitation nexte ester’